The lives of our female ancestors are frequently neglected by family historians. As I’ve researched my maternal ancestry, I’ve been impressed with the women in my family, who, like many women, led remarkably difficult and heroic lives that have gone largely unremembered and unrecorded. One of these women is Janet Sellars, my Scots great-great-grandmother.

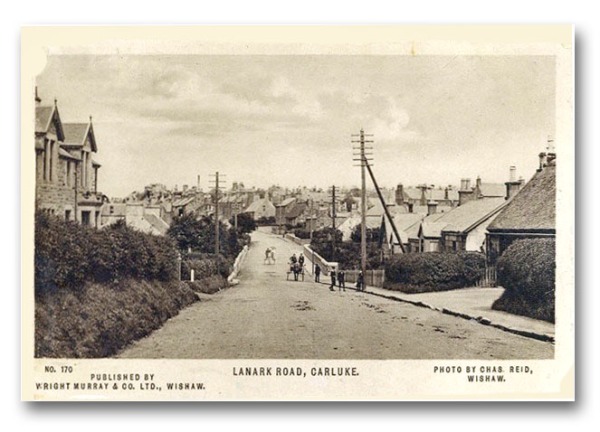

Janet was the daughter of a cotton weaver, the wife of a wagon driver, and the mother of eight children. She was born on January 25, 1823, the only known daughter of John and Margaret (Mackay or Mackie) Sellars, who had three other known sons. The family lived about 20 miles southeast of Glasgow in the village of Carluke, near the Clyde River in central Lanarkshire. Janet was a popular name in Scotland in that era and the name and its derivatives, Jessie and Jean, show up in many branches of my maternal family.

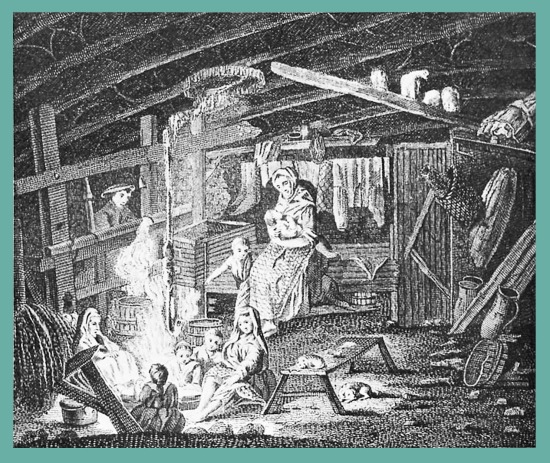

An Etching of a Weaver’s Cottage

When Janet was born, Carluke was a prominent cotton-weaving center with about 400 residents, the majority involved in some aspect of the cotton industry that would continue to flourish for another 40 years. Nearly all weavers’ cottages had a hand-loom, for the production of textiles was typically a family enterprise. The men nearly always worked the looms, while the women and children contributed by winding pins or doing needlework and embroidery. It’s likely that Margaret taught young Janet the requisite needle skills to be useful, for the Sellars children would not have attended school. While Parliament passed a law regulating child labor in factories in 1833, such laws did not apply to families working from their homes in rural villages, where there was simply no time or opportunity for luxuries like schooling.

Janet was 21 when she married 31-year-old John Clark on November 28, 1844, in Wishaw, a coal mining town about five miles from where Janet was born. John was from the village of Fenwick in Ayrshire, a fertile agricultural area on the Firth of Clyde. (See map below.) His parents were James Clark and Marion Wylie. The Wylie family has been traced back to the 1500s. Some were large landowners in the Stewarton area.

Following their marriage, the Clarks lived in Wishaw and raised eight children, evenly divided between the sexes, over the next 18 years. They followed the Scottish naming pattern of that era, naming their eldest son James, after John’s father, their eldest daughter Margaret, after Janet’s mother, the next daughter Marion, after John’s mother, and their fourth child John, after Janet’s father. They named their other children Janet, Robert, and Isabella. Unfortunately, another son, born on 1858, has never been identified by name.

John Clark supported his large family as a wagon driver. He may have driven the 44-mile round trip to Glasgow early in his career. When the railroad came to Wishaw in the 1840s, his work likely became more local. It had to have been a repetitive, tiring job, requiring physical strength. His temperament may have been well suited for such labor, for once the wagon was loaded, he had time to himself, navigating the dusty roads alone, the Scottish sun rarely too hot. It was his life’s work until he reached the age of forty-nine. Then tragedy struck. Continue reading